The calls come thick and fast to Mumbai-based diabetologist Rahul Baxi - but not just from patients struggling to control blood sugar.

Increasingly, it is young professionals asking the same thing: Doctor, can you start me on weight-loss drugs?

Recently, a 23-year-old man came in, worried about the 10kg he'd gained after starting a demanding corporate job. One of my gym friends is on [weight loss] jabs, he said.

Dr Baxi says he refused, asking him what he would do after losing 10kg on the drug. Stop, and the weight comes back. Keep going, and without exercise you'll start losing muscle instead. These medicines aren't a substitute for a proper diet or lifestyle change, he told him.

Such conversations are becoming increasingly common as demand for weight-loss drugs explodes in urban India - a country with the world's second-largest number of overweight adults and more than 77 million people with Type 2 diabetes. Originally developed to treat diabetes, these drugs are now being hailed as game changers for weight loss, offering results that few previous treatments could match. Yet their growing popularity has also raised difficult questions - about the need for medical supervision, the risks of misuse and the blurred line between treatment and lifestyle enhancement.

These are the most powerful weight-loss drugs we've ever seen. Many such drugs have come and gone, but nothing compares to these, says Anoop Misra, who heads Delhi's Fortis-C-DOC Centre of Excellence for Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases and Endocrinology.

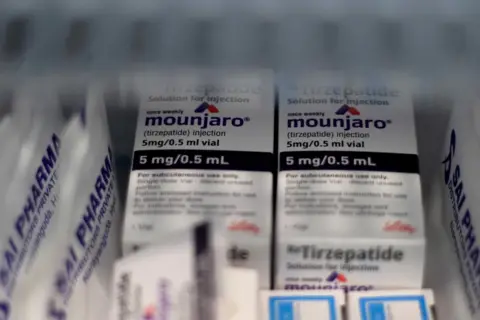

Two new drugs dominate India's fast-growing weight-loss market: semaglutide, sold by Novo Nordisk as Rybelsus (oral) and Wegovy (injectable), and tirzepatide, marketed by Eli Lilly as Mounjaro, primarily for diabetes but increasingly used for weight loss in India. Both belong to a class known as GLP-1 drugs, which mimic a natural hormone that regulates hunger. By slowing digestion and acting on the brain's appetite centres, they make people feel full faster and stay full longer. Taken once a week, most of these drugs are self-injected in the arm, thigh or stomach. They curb cravings - and in Mounjaro's case, also boost metabolism and energy balance.

Treatment starts with a low dose that's slowly raised to a maintenance level, and weight loss usually begins within weeks. However, doctors warn that most users can regain weight within a year of stopping, as the body resists weight loss and old cravings return. Prolonged use without exercise or strength training can also strip away muscle along with fat. Not everyone responds to GLP-1 drugs, and most plateau after losing about 15% of their body weight. Side effects range from nausea and diarrhoea to rarer risks such as gallstones, pancreatitis, and muscle loss. India's high-carb, low-protein diet already fuels sarcopenic obesity - the loss of muscle alongside fat gain - and weight loss without adequate protein or exercise can make it worse.

With all the media hype and social media buzz, these drugs have become something of a craze among affluent Indians eager to shed a few kilos, says Dr Baxi.

India's anti-obesity drug market has surged from $16m in 2021 to nearly $100m today - a more than sixfold jump in five years, according to Pharmarack, a research firm. Novo Nordisk leads the market with its semaglutide brands, which account for nearly two-thirds of the market since their launch. Eli Lilly's tirzepatide, launched earlier this year, became India's second-bestselling branded drug by September. Each monthly injectable pen costs between 14,000-27,000 rupees ($157–300), which is steep for most Indians.

What India has seen so far may just be the tip of the iceberg. The patent for semaglutide is set to expire, potentially leading to a surge of cheaper generics. Doctors warn this increased accessibility may lead to higher misuse rates and concerns over prescription legitimacy. Some patients are already receiving prescriptions from unqualified professionals, illustrating a breakdown in regulatory oversight.

Obesity is often perceived in a cultural context that sees it as a sign of affluence, complicating public health messaging. However, with increasing awareness and the advent of new treatments, obesity is slowly being recognized as a chronic disease that requires medical intervention.

As the landscape around weight loss drugs continues to evolve, doctors across various specialties are now increasingly addressing the issue of obesity not only for cosmetic reasons but for life-threatening health challenges.