NEW YORK (AP) — After fleeing a brutal civil war in Sierra Leone and spending nearly a decade in a refugee camp, Dauda Sesay arrived in the United States with dreams of a new life. He was initially unaware that he could become a citizen, but soon learned that by adhering to the laws and staying out of trouble, he could potentially apply for naturalization. The promise of citizenship came with the agency and protection that belied his traumatic past.

Motivated by the belief that through naturalization he would forge a meaningful bond with his newfound home, Sesay, now 44, took the oath of allegiance and felt a sense of belonging. Now living in Louisiana and working as a refugee advocate, he once saw his U.S. citizenship as a commitment that secured both rights and responsibilities in the eyes of his adopted country.

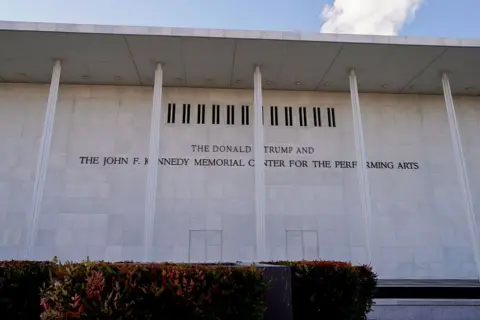

However, recent months have shaken this belief for Sesay and other naturalized citizens as the Trump administration implements stark changes to immigration policies. The increasing focus on deportation measures and attempts to redefine who can claim American identity, such as moves to end birthright citizenship, cast a shadow over their sense of security.

For many, what was once a solid foundation of naturalization now feels unstable. Citizens like Sesay worry about the repercussions of traveling abroad or even within the country, fearing they might be questioned or detained by border agents.

“I no longer travel domestically without my passport, even though I have a REAL ID,” Sesay shared, underscoring a new climate of anxiety about even the most basic rights of travel that naturalized citizens thought were guaranteed.

This fear is further exacerbated by recent reports of naturalized citizens being swept up in immigration enforcement operations, with some U.S. citizens saying they have been detained on the suspicion of being undocumented. This unsettling atmosphere prompted the Department of Justice to announce enhanced efforts to denaturalize immigrants deemed a national security risk—a move that has raised alarms across immigrant communities.

State Sen. Cindy Nava of New Mexico relates to these fears, having grown up undocumented before securing her own citizenship through marriage. She reveals that many of her previously unafraid friends are now grappling with anxiety about their status and the trust they once placed in their citizenship.

The concept of citizenship has indeed evolved over American history, with past definitions excluding entire groups based on race or ethnicity. Stephen Kantrowitz, a history professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, notes the ambiguous nature of citizenship within the U.S. Constitution, stating that at its inception, it was undefined and subject to interpretation.

Historical laws reflecting exclusionary practices have ebbed and flowed, from the initial naturalization law that limited citizenship to “free white persons” in 1790 to the 1924 Immigration Act that barred Asian individuals from citizenship. It took until 1952 for those racial barriers to be lifted, reflecting a gradual redefinition of what it means to be an American.

Despite the progress, moments in history have also witnessed the stripping of citizenship rights, such as during World War II with the internment of Japanese Americans. For Sesay, this ongoing shift in immigration policy feels like a betrayal of the commitment he made to the country he now calls home.

“This is not the America I believe in when I put my hand over my heart,” he concluded, showcasing the emotional turmoil faced by those whose identities as citizens suddenly seem tenuous. As the struggles of naturalized citizens come to the forefront, it is clear that the fight for the promise of citizenship continues amidst changing tides in policy and perception.