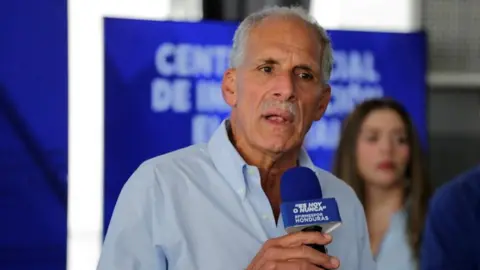

For over a year, Elías Padilla had been saving up to make the journey from Honduras to the United States as an undocumented immigrant. As an Uber driver in the snarled streets of the capital, Tegucigalpa, it hasn't been easy for him to put money aside. On bad days he makes as little as $12 (£9) in 12 hours. Now, though, his plans are on hold. The images of undocumented immigrants in major U.S. cities being dragged away by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, their wrists in zip-ties, have deterred at least one would-be immigrant in Central America from traveling north. I want to improve my life conditions because we earn very little here, Elías explains as we drive around the city. Take this line of work, for example: an Uber driver in the U.S. makes in an hour what I'd make in a day. Like most Honduran immigrants, Elías says the main aim of reaching the U.S. would be to send remittances home. But I see what Trump is doing, and it's made me think twice, he admits. I'm going to wait to see what the change in government here brings, he says, referring to the recent presidential election. Hopefully things will improve. Elías's change of heart is welcomed by architects of President Trump's immigration policies, whose operations intended to deter immigration have had unexpected economic impacts. Between January and October 2025, remittances to Honduras rose by 26% compared to the previous year, showing that many undocumented Hondurans are sending every spare dollar back to their families as they fear for their futures. Marcos, an undocumented worker in construction, shares that he increasingly sends more money home for basic needs, pushing remittance amounts from $500 a month to $300 weekly, illustrating that for many, the race against time is not just about survival, but also about ensuring support remains stable for their families amid uncertainty.

Hondurans in the U.S. Increase Remittances Amid Fear of Deportation

Hondurans in the U.S. Increase Remittances Amid Fear of Deportation

Honduran immigrants in the United States are sending more money back home than ever before, driven by the fear of deportation and ongoing ICE operations. Despite the challenges, remittances have surged as families prepare for uncertain futures.

In light of escalating fears of deportation due to strict immigration policies, Hondurans residing in the United States are dramatically increasing their remittances back home. Many undocumented immigrants are sending more money to support their families as a buffer against potential detention, reflecting the ongoing strain of strict U.S. immigration enforcement under the Trump administration. Significant changes in the remittance patterns showcase the economic impact of political decisions on the lives of Central American migrants.