Just over two years ago, when Sheikh Hasina won an election widely condemned as rigged in her favour, it was hard to imagine her 15-year grip on power being broken so suddenly, or that a rival party that had been virtually written off would make such a resounding comeback.

But in the cycle of Bangladeshi politics, this is one more flip-flop between Hasina's Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which have alternated holding power for decades.

Except this is the first time that new BNP leader Tarique Rahman is formally leading the party - and the first time he's contested an election.

His mother Khaleda Zia, who died of an illness late last year, was the party's head for four decades. She took over after his father, Ziaur Rahman, the BNP founder and a key leader of Bangladesh's war for independence, was assassinated.

Accused of benefitting from nepotism when his mother was in power, Tarique Rahman has also faced allegations of corruption. Five days before his mother died, he returned to Bangladesh after 17 years of self-imposed exile in London.

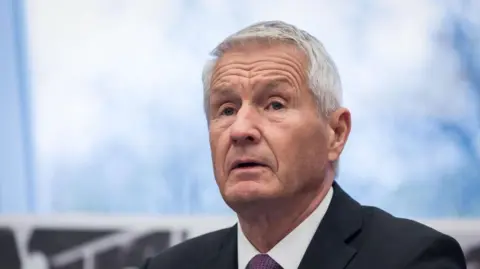

Rahman, 60, has on occasion been the de-facto chair of an emaciated BNP when his mother was jailed and more recently when she was ill, but he's largely seen as an untested leader.

That he doesn't have prior experience probably works for him, because people are willing to give change a chance, says political scientist Navine Murshid. They want to think that new, good things are actually possible. So there is a lot of hope.

The party says its first priority is to bring democracy back to Bangladesh. All the democratic institutions [and] financial institutions, which have been destroyed over the last decade, we have to first put those back in order, senior BNP leader Amir Khasru Mahmud Chowdhury told the BBC shortly after the election was called.

However, history suggests such promises often go unfulfilled, with parties becoming increasingly authoritarian once they come to power. The current youth generation, responsible for the 2024 'July uprising' that ousted Hasina, appears less willing to accept the status quo.

We don't want to fight again, says Tazin Ahmed, a 19-year-old who participated in the uprising. The stepping down of the previous prime minister was not the victory. When our country runs smoothly without any corruption, and the economy becomes good, that will be our main victory.

Since Hasina was ousted, violence has marred the tenure of Bangladesh's interim leader Mohammad Yunus. The new government will face the urgent tasks of ensuring law and order, addressing inflation, creating jobs for the burgeoning youth population, and establishing a transparent governance system.

Despite his lack of direct experience, Rahman has the chance to carve out a new vision for Bangladesh. Yet the steep challenges ahead leave many wondering if he can meet the lofty expectations set by a populace yearning for genuine democratic reform.

}