India has ordered all new smartphones to come pre-loaded with a state-run cybersecurity app, sparking privacy and surveillance concerns. Under the order - passed last week but made public on Monday - smartphone makers have 90 days to ensure all new devices come with the government's Sanchar Saathi app, whose functionalities cannot be disabled or restricted.

This move is deemed necessary to help citizens verify the authenticity of a handset and report the suspected misuse of telecom resources. However, it has drawn criticism from cyber experts who argue that it breaches citizens' right to privacy.

Under the app's privacy policy, it can make and manage phone calls, send messages, access call and message logs, photos and files, as well as the phone's camera. The advocacy group Internet Freedom Foundation noted that this effectively converts smartphones into vessels for state-mandated software that users cannot meaningfully refuse, control, or remove.

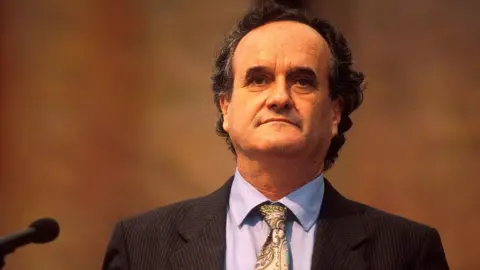

Communications Minister Jyotiradtiya Scindia attempted to alleviate concerns by asserting that users would have the option to delete the app if they do not wish to use it. However, the minister did not clarify how users could delete an app whose functions cannot be disabled or restricted.

Launched in January, the Sanchar Saathi app allows users to check a device's IMEI, report lost or stolen phones, and flag suspected fraud communications. The IMEI is a unique code that identifies and authenticates a mobile device on cellular networks, akin to a phone's serial number.

The Indian government insists that the initiative will bolster telecommunications cybersecurity, citing recovery of over 700,000 lost phones as evidence of its effectiveness. Nonetheless, privacy advocates worry about the extensive data collection capabilities of the app, which has raised alarms about potential overreach and misuse of personal information.

Experts also point out the challenges of compliance with the new order, as it contradicts the policies of major handset manufacturers, such as Apple, which prohibits pre-installation of third-party applications, including those mandated by the government.

India's smartphone market features approximately 1.2 billion mobile subscribers, and analysts predict that compliance with this mandate could create significant upheaval in device sales and user trust in technology. This situation mirrors measures taken in other countries, such as Russia, which also mandated pre-installed state-backed applications on mobile devices.

This move is deemed necessary to help citizens verify the authenticity of a handset and report the suspected misuse of telecom resources. However, it has drawn criticism from cyber experts who argue that it breaches citizens' right to privacy.

Under the app's privacy policy, it can make and manage phone calls, send messages, access call and message logs, photos and files, as well as the phone's camera. The advocacy group Internet Freedom Foundation noted that this effectively converts smartphones into vessels for state-mandated software that users cannot meaningfully refuse, control, or remove.

Communications Minister Jyotiradtiya Scindia attempted to alleviate concerns by asserting that users would have the option to delete the app if they do not wish to use it. However, the minister did not clarify how users could delete an app whose functions cannot be disabled or restricted.

Launched in January, the Sanchar Saathi app allows users to check a device's IMEI, report lost or stolen phones, and flag suspected fraud communications. The IMEI is a unique code that identifies and authenticates a mobile device on cellular networks, akin to a phone's serial number.

The Indian government insists that the initiative will bolster telecommunications cybersecurity, citing recovery of over 700,000 lost phones as evidence of its effectiveness. Nonetheless, privacy advocates worry about the extensive data collection capabilities of the app, which has raised alarms about potential overreach and misuse of personal information.

Experts also point out the challenges of compliance with the new order, as it contradicts the policies of major handset manufacturers, such as Apple, which prohibits pre-installation of third-party applications, including those mandated by the government.

India's smartphone market features approximately 1.2 billion mobile subscribers, and analysts predict that compliance with this mandate could create significant upheaval in device sales and user trust in technology. This situation mirrors measures taken in other countries, such as Russia, which also mandated pre-installed state-backed applications on mobile devices.