Shirley Chung was just a year old when she was adopted by a US family in 1966.

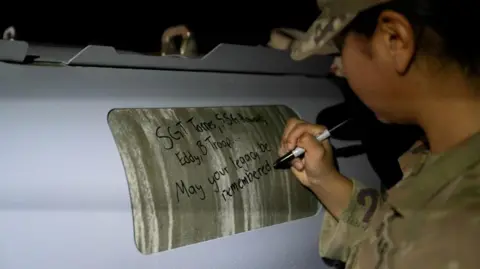

Born in South Korea, her birthfather was a member of the American military, who returned home soon after Shirley was born. Unable to cope, her birth mother placed her in an orphanage in the South Korean capital, Seoul.

He abandoned us, is the nicest way I can put it, says Shirley, now 61.

After around a year, Shirley was adopted by a US couple, who took her back to Texas.

Shirley grew up living a life similar to that of many young Americans. She went to school, got her driving licence and worked as a bartender.

I moved and breathed and got in trouble like many teenage Americans of the 80s. I'm a child of the 80s, Shirley says.

Shirley had children, got married and became a piano teacher. Life carried on for decades with no reason to doubt her American identity.

But then in 2012, her world came crashing down.

She lost her Social Security card and needed a replacement. But when she went to her local Social Security office, Shirley was told she needed to prove her status in the country. Eventually she found out she did not have US citizenship.

I had a little mental breakdown after finding out I wasn't a citizen, she says.

Shirley is not alone. Estimates of how many American adoptees lack citizenship range from 18,000 to 75,000. Some intercountry adoptees may not even know they lack US citizenship.

Dozens of adoptees have been deported to their countries of birth in recent years, according to the Adoptee Rights Law Center. A man born in South Korea and adopted as a child by an American family - only to be deported to his country of birth because of a criminal record - took his own life in 2017.

The reasons why so many US adoptees do not have citizenship are varied. Shirley blames her parents for failing to finalise the correct paperwork when she came to the US. She also blames the school system and the government for not highlighting that she did not have citizenship.

I blame all the adults in my life that literally just dropped the ball and said: 'She's here in America now, she's going to be fine.'

Well, am I? Am I going to be fine?

Another woman, who requested anonymity for fear of attracting the attention of authorities, was adopted by an American couple from Iran in 1973 when she was two years old.

Growing up in the US Midwest, she encountered some racism but generally had a happy upbringing.

I settled into my life, always understanding that I was an American citizen. That's what I was told. I still believe that today, she says.

But that changed when she tried to get a passport at the age of 38 and discovered immigration authorities had lost critical documents that supported her claim to citizenship.

This has further complicated her feelings surrounding identity.

I personally don't categorise myself as an immigrant. I didn't come here as an immigrant with a second language, a different culture, family members, ties to a country that I was born in… my culture was erased, she says.

For decades, intercountry adoptions approved by courts and government agencies did not automatically guarantee US citizenship. Adoptive parents sometimes failed to secure legal status or naturalised citizenship for their children.

The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 made some headway in rectifying this, granting automatic citizenship to international adoptees. But the law only covered future adoptees or those born after February 1983. Those who arrived before then were not granted citizenship, leaving tens of thousands in limbo.

Advocates have been pushing for Congress to remove the age cut-off but these bills have failed to make it past the House.

The recent political climate has heightened fears for adoptees like Shirley and others, as they face the uncertainty of potential deportations under stricter immigration policies. As stories of adoptee struggles and identities unfold, many hope for a resolution that acknowledges the rights of those they believed were American citizens.