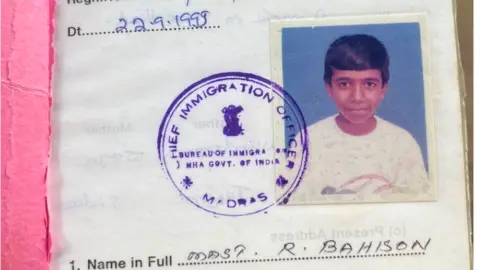

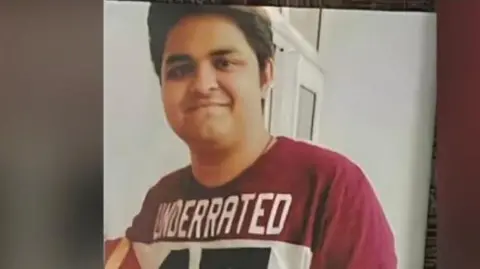

Bahison Ravindran says he always believed he was Indian. Born to Sri Lankan refugee parents in the southern Indian Tamil Nadu state, the 34-year-old web developer had studied and worked there, and held several government-issued identity documents, including an Indian passport.

But a rude shock awaited him in April when police arrested him, saying his passport was invalid. Authorities said he was not an Indian 'citizen by birth' since both his parents were Sri Lankans who had fled to India in 1990 amid the civil war there.

For long, anyone born in India qualified for Indian citizenship, but a 1987 amendment to the law required at least one parent to be an Indian citizen for a child born after 1 July of that year to qualify.

Mr. Ravindran, who was born in 1991 within months of his parents' arrival in India, told the Madras High Court in Chennai last week that he was unaware of the rule and had never hidden his ancestry from authorities. He also told the court that as soon as he was informed that 'citizenship by birth' was not automatic in India, he immediately applied for 'citizenship through naturalisation'.

But for now, he has become 'stateless'. His unique situation spotlights the plight of thousands of Sri Lanka's Tamil refugees in India who fled the island nation during its decades-long conflict in the 1980s. More than 90,000 of them live in the southern state, both in refugee camps and outside, according to the Tamil Nadu government.

And now there are more than 22,000 individuals like Mr. Ravindran, who were born in India after 1987 to Sri Lankan Tamil parents. These individuals often find their citizenship status remains in limbo due to the legal framework.

Part of the reason is that India is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention or its 1967 protocol and considers Sri Lankan refugees as illegal migrants. The 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which fast-tracks applications from persecuted non-Muslim minorities from India's neighbouring countries, also excludes Tamils from Sri Lanka.

The status of Sri Lankan Tamils is an emotive subject in the state, with different political parties promising to help resolve their citizenship concerns. However, for most, it remains a distant dream.

Mr. Ravindran hopes his case will be taken up soon. He pledges allegiance to India and says he never intends to return to Sri Lanka. He recently told the BBC that he has travelled to the island nation just once in his life – in September 2024 to marry a Sri Lankan woman.

His troubles began after he applied for a fresh passport to include the name of his spouse this year. Despite initially receiving a new passport, authorities later flagged his parents' origin.

Mr. Ravindran was arrested last month on charges of cheating and forgery and was held in custody for 15 days before being freed on bail. He fears further punitive action, and the case now rests with the Madras High Court, where he seeks acknowledgment of his status as a citizen.

But a rude shock awaited him in April when police arrested him, saying his passport was invalid. Authorities said he was not an Indian 'citizen by birth' since both his parents were Sri Lankans who had fled to India in 1990 amid the civil war there.

For long, anyone born in India qualified for Indian citizenship, but a 1987 amendment to the law required at least one parent to be an Indian citizen for a child born after 1 July of that year to qualify.

Mr. Ravindran, who was born in 1991 within months of his parents' arrival in India, told the Madras High Court in Chennai last week that he was unaware of the rule and had never hidden his ancestry from authorities. He also told the court that as soon as he was informed that 'citizenship by birth' was not automatic in India, he immediately applied for 'citizenship through naturalisation'.

But for now, he has become 'stateless'. His unique situation spotlights the plight of thousands of Sri Lanka's Tamil refugees in India who fled the island nation during its decades-long conflict in the 1980s. More than 90,000 of them live in the southern state, both in refugee camps and outside, according to the Tamil Nadu government.

And now there are more than 22,000 individuals like Mr. Ravindran, who were born in India after 1987 to Sri Lankan Tamil parents. These individuals often find their citizenship status remains in limbo due to the legal framework.

Part of the reason is that India is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention or its 1967 protocol and considers Sri Lankan refugees as illegal migrants. The 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which fast-tracks applications from persecuted non-Muslim minorities from India's neighbouring countries, also excludes Tamils from Sri Lanka.

The status of Sri Lankan Tamils is an emotive subject in the state, with different political parties promising to help resolve their citizenship concerns. However, for most, it remains a distant dream.

Mr. Ravindran hopes his case will be taken up soon. He pledges allegiance to India and says he never intends to return to Sri Lanka. He recently told the BBC that he has travelled to the island nation just once in his life – in September 2024 to marry a Sri Lankan woman.

His troubles began after he applied for a fresh passport to include the name of his spouse this year. Despite initially receiving a new passport, authorities later flagged his parents' origin.

Mr. Ravindran was arrested last month on charges of cheating and forgery and was held in custody for 15 days before being freed on bail. He fears further punitive action, and the case now rests with the Madras High Court, where he seeks acknowledgment of his status as a citizen.