Donald Trump swept back into the White House this year promising, among other things, retribution against his perceived enemies. Nine months later, the unprecedented scope of that pledge – or threat – is fully taking shape.

Trump has vocally encouraged his attorney general to target political opponents. He has suggested the government should revoke TV licenses to bring a biased mainstream media to heel. He has targeted law firms he sees as adversaries, pulling government security clearances and contracts.

His moves have been conducted with the kind of open zeal – brazenness, his critics say – that might belie how dramatic and norm-shattering they are.

His demand a week ago that the Justice Department prosecute a handful of named political opponents, for instance, is the kind of thing that, when it was discussed in private and revealed in Oval Office recordings a half-century ago, prompted a bipartisan outcry that led to Richard Nixon's resignation as president.

Now it is just a blip in the weekly news cycle. And the pace at which Trump is expanding presidential authority in order to impose his will is, if anything, accelerating.

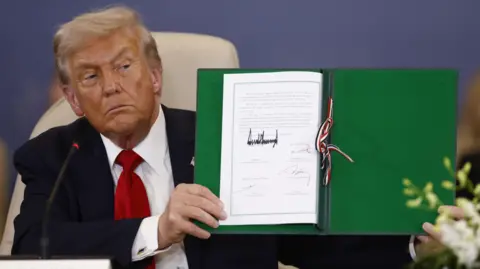

On Thursday, Trump signed an order on 'domestic terrorism and political violence', saying it would be used to investigate 'wealthy people' who fund 'professional anarchists and agitators'. He suggested liberal billionaires George Soros and LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman could be among them.

Then hours later, Trump's Justice Department announced it had indicted James Comey, the former FBI director and Trump critic whom the president had said was 'guilty as hell' days earlier.

Trump has justified a looming crackdown on left-wing groups by pointing to two recent, and shocking, acts of violence. First, the killing of conservative activist Charlie Kirk on a college campus, and then this week's gun attack targeting immigration agents in Dallas, in which two migrant detainees were wounded, and one killed.

The president says his broader blitz of action is necessary, and urgent. The investigations of political opponents, he says, are about targeting law-breakers and members of the 'deep state' who undermined his first presidential term.

The mainstream media, in the view of his MAGA coalition, should be held to account over alleged bias and 'fake news'. Private businesses weakened by diversity policies and political corruption require the firm hand of government to set them straight.

During the Democrat's four years in office, Trump was indicted four times and convicted once. Several of his close aides – including former 2016 campaign chair Steve Bannon and trade adviser Peter Navarro – were prosecuted and imprisoned for contempt of Congress. Others were indicted for their alleged role in attempting to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

The Biden White House directed social media companies to restrict what it characterized as harmful speech during the Covid pandemic. And the president attempted to expand presidential powers to implement his agenda, including student loan forgiveness, vaccine mandates, protection of transgender rights in public schools, and environmental regulation.

While Trump was prosecuted, only two of the cases were brought by the federal government and both by a special prosecutor set up to be independent of Biden's justice department.

Biden, unlike Trump, remained largely silent about the cases. Many of Biden's executive actions were undone by the Supreme Court, which so far has given Trump a free hand to operate.

Underlying the entirety of the debate about presidential power and 'retribution' has been a fundamental disagreement between Biden and Trump over the nature of the existential dangers facing America and the world.