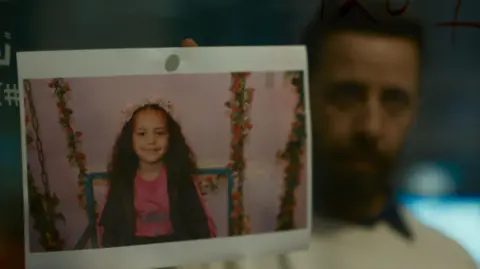

When Keira's daughter was born last November, she was given two hours with her before the baby was taken into care. Right when she came out, I started counting the minutes, Keira, 39, recalls. I kept looking at the clock to see how long we had. When the moment came for Zammi to be taken from her arms, Keira says she sobbed uncontrollably, whispering sorry to her baby. It felt like a part of my soul died. Now Keira is one of many Greenlandic families living on the Danish mainland who are fighting to get their children returned to them after they were removed by social services. In such cases, babies and children were taken away after parental competency tests - known in Denmark as FKUs - were used to help assess whether they were fit to be parents. In May this year, the Danish government banned the use of these tests on Greenlandic families after decades of criticism, although they continue to be used on other families in Denmark. The assessments, which usually take months to complete, are used in complex welfare cases where authorities believe children are at risk of neglect or harm. They include interviews with parents and children, a range of cognitive tasks, such as recalling a sequence of numbers backwards, general knowledge quizzes, and personality and emotional testing. Defenders of the tests say they offer a more objective method of assessment than the potentially anecdotal and subjective evidence of social workers and other experts. But critics say they cannot meaningfully predict whether someone will make a good parent. Opponents have also long argued that they are designed around Danish cultural norms and point out they are administered in Danish, rather than Kalaallisut, the mother tongue of most Greenlanders. This can lead to misunderstandings, they say. Greenlanders are Danish citizens, enabling them to live and work on the mainland. Thousands live in Denmark, drawn by its employment opportunities, education, and healthcare, among other reasons. Greenlandic parents in Denmark are 5.6 times more likely to have children taken into care than Danish parents, according to the Danish Centre for Social Research, a government-funded research institute. In May, the government said it hoped in due course to review around 300 cases – including ones involving FKU tests – in which Greenlandic children were forcibly removed from their families. But as of October, the BBC found that just 10 cases where parenting tests were used had been reviewed by the government - and no Greenlandic children had been returned as a result. Keira's assessment in 2024, carried out when she was pregnant, concluded that she did not have sufficient parental competencies to care for the newborn independently. Keira says the questions she was asked included: Who is Mother Teresa? and How long does it take for the sun's rays to reach the Earth? Psychologists who defend the tests argue questions like these are intended to assess parents' general knowledge and their understanding of concepts they might encounter in society. Keira adds that they made me play with a doll and criticised me for not making enough eye contact. She alleges that when she asked why she was being tested in this way the psychologist told her: To see if you are civilised enough, if you can act like a human being. The local authority in Keira's case said it could not comment on individual families, adding that decisions to place a child in care were made when there was serious concern about the child's health, development, and well-being. In 2014, Keira's other two children - who were then aged nine years and eight months - were placed into care after an FKU test at the time concluded her parenting skills were not developing fast enough to meet their needs. Her eldest, Zoe, who is now 21, moved back home when she was 18 and currently lives in her own apartment and sees her mum regularly. Keira hopes she will soon be reunited with her baby Zammi permanently. The Danish government has said its review will look at whether mistakes were made in the administering of FKU tests on Greenlandic people. In the meantime, Keira is allowed to see Zammi, who is in foster care, once a week for an hour. Each time she visits, she takes flowers and sometimes Greenlandic food, such as chicken heart soup. Just so a little part of her culture can be with her, she says.

Struggles of Greenlandic Parents: Fighting for Children Taken After Controversial Tests

Struggles of Greenlandic Parents: Fighting for Children Taken After Controversial Tests

Greenlandic families in Denmark battle to reunite with their children taken by social services following biased parental competency tests. Insights into their heart-wrenching stories and the impact of cultural misunderstandings emerge.

This article highlights the emotional turmoil faced by Greenlandic parents in Denmark whose children were taken away following parental competency tests deemed biased. Keira's story reflects the heartbreak and frustration of many as they navigate the complex social welfare system that has disproportionately targeted their community. The government's recent ban on the controversial testing does not currently assist all affected families, leaving many seeking justice and reunion with their children.