In the complex mosaic of the new Syria, the old battle against the group calling itself Islamic State (IS) continues in the Kurdish-controlled north-east. It's a conflict that has slipped from the headlines - with bigger wars elsewhere.

Kurdish counter-terrorism officials have told the BBC that IS cells in Syria are regrouping and increasing their attacks.

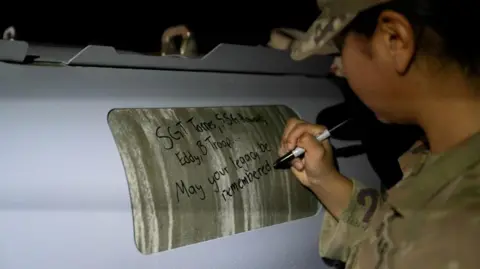

Walid Abdul-Basit Sheikh Mousa was obsessed with motorbikes and finally managed to buy one in January. The 21-year-old only had a few weeks to enjoy it. He was killed in February fighting against IS in north-eastern Syria.

Walid was so keen to take on the extremists that he ran away from home, aged 15, to join the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). They brought him back because he was a minor, but accepted him three years later.

Generations of his extended family gathered in the yard of their home in the city of Qamishli to tell us about his short life.

I see him everywhere, said his mother, Rojin Mohammed. He left me with so many memories. He was very caring and affectionate.

Instead, the Islamic State Group is recruiting and reorganising - according to Kurdish officials, taking advantage of a security vacuum after the ousting of Syria's long-time dictator Bashar al-Assad last December.

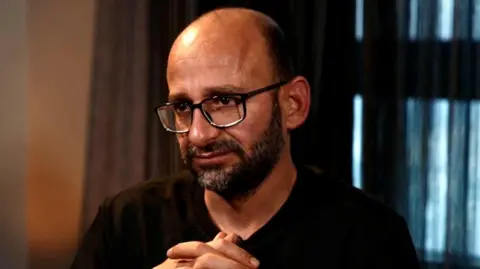

There's been a 10-fold increase in their attacks, says Siyamend Ali, a spokesman for the People's Protection Units (YPG) - a Kurdish militia, which has been fighting IS for over a decade, and is the backbone of the SDF.

Kurdish authorities have their hands - and jails - full with suspected IS fighters. Around 8,000 - from 48 countries including the UK, the US, Russia and Australia - have been held for years in a network of prisons in the north east.

The largest jail for IS suspects is al-Sina in the city of Al Hasakah - ringed by high walls, and watch towers.

Some detainees wear disposable masks to prevent the spread of infection. Tuberculosis is their companion in al-Sina, where they are being held indefinitely.

He says the militants have expanded their areas of operation and methods of attack. They have graduated from hit-and-run operations to attacking checkpoints and planting landmines.

After years in jail, some detainees plead to return to their home countries. However, countries like Britain are in no hurry to do that.

In large tented camps in the desert, families of IS fighters live in harsh conditions, many denied fundamental rights. Human rights groups classify this as collective punishment.

We are worried about the children, said the camp manager, echoing fears that the next generation will inherit the ideology that led their parents into violence.

As the region grapples with rising violence and the shadow of ISIS, the future remains uncertain for both the prisoners and those they left behind.