In the heart of the South Pacific, the Cook Islands face a critical decision that could shape their future. Under the tutelage of Prime Minister Mark Brown, the government is advocating for the extraction of polymetallic nodules located deep within their territorial waters, a potential economic windfall packed with metals essential for modern technology. However, these plans have sparked fierce opposition from environmental activists and local communities, fearing irreversible damage to fragile marine ecosystems.

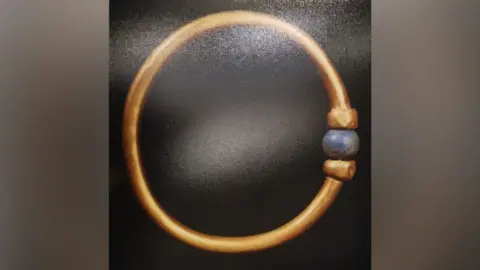

Jean Mason, curator of the Cook Islands Library and Museum, illustrates the allure of these nodules, playful in her description likening them to chocolate truffles. Historically overlooked, these nodules—rich in cobalt, nickel, and manganese—are now seen as an economic lifeline at a time when tourism revenues have faltered due to the pandemic and rising sea levels threaten the islands' very existence. The Seabeds Minerals Authority of the Cook Islands estimates a staggering 12 billion wet tonnes of nodules within their economic zone.

Prime Minister Brown is enthusiastic, believing these resources could usher in a new era of prosperity, enabling locals to access higher education and modern healthcare without financial burdens. He envisions a sovereign wealth fund akin to Norway's, which would leverage resource profits for the nation’s benefit. However, the juxtaposition of economic necessity against environmental stewardship complicates the narrative.

Critics argue that the ecological risks associated with deep-sea mining are profound and still largely unknown. As advocates call for a moratorium on such activities until comprehensive research assesses the environmental impact, protesters have taken to the seas, urging greater caution. Activist Alanah Matamaru Smith emphasizes the need for independent studies and community awareness of the potential risks.

Despite the government's assurances, dissent is brewing. Opposition voices, like those of June Hosking, highlight the discontent that simmers beneath the surface in the outer islands, voicing concerns that consultation processes lack genuine discourse and oversight.

This climate of uncertainty raises a pivotal question: Is the drive to mine the ocean floor a reasonable step toward self-sufficiency, or an uncontrollable rush toward profit that endangers the very heritage of the Cook Islands? As the government pushes forward, the dialogue about economic survival and environmental integrity rages on, suggesting that the future of this nation hangs in a delicate balance.

All eyes remain on the Cook Islands—a laboratory for a global conversation on resource extraction, ecological preservation, and the deep-seated values held by island communities. Yet, as exploration licenses are granted and discussions progress, the stakes remain high, embodying the intricate dance between opportunity and responsibility in the realm of deep-sea mining.

Thus, the quest to extract ocean riches persists, packed with hopes and fears, shedding light on the broader implications of how developing nations choose to navigate their futures amidst the waves of change.

Jean Mason, curator of the Cook Islands Library and Museum, illustrates the allure of these nodules, playful in her description likening them to chocolate truffles. Historically overlooked, these nodules—rich in cobalt, nickel, and manganese—are now seen as an economic lifeline at a time when tourism revenues have faltered due to the pandemic and rising sea levels threaten the islands' very existence. The Seabeds Minerals Authority of the Cook Islands estimates a staggering 12 billion wet tonnes of nodules within their economic zone.

Prime Minister Brown is enthusiastic, believing these resources could usher in a new era of prosperity, enabling locals to access higher education and modern healthcare without financial burdens. He envisions a sovereign wealth fund akin to Norway's, which would leverage resource profits for the nation’s benefit. However, the juxtaposition of economic necessity against environmental stewardship complicates the narrative.

Critics argue that the ecological risks associated with deep-sea mining are profound and still largely unknown. As advocates call for a moratorium on such activities until comprehensive research assesses the environmental impact, protesters have taken to the seas, urging greater caution. Activist Alanah Matamaru Smith emphasizes the need for independent studies and community awareness of the potential risks.

Despite the government's assurances, dissent is brewing. Opposition voices, like those of June Hosking, highlight the discontent that simmers beneath the surface in the outer islands, voicing concerns that consultation processes lack genuine discourse and oversight.

This climate of uncertainty raises a pivotal question: Is the drive to mine the ocean floor a reasonable step toward self-sufficiency, or an uncontrollable rush toward profit that endangers the very heritage of the Cook Islands? As the government pushes forward, the dialogue about economic survival and environmental integrity rages on, suggesting that the future of this nation hangs in a delicate balance.

All eyes remain on the Cook Islands—a laboratory for a global conversation on resource extraction, ecological preservation, and the deep-seated values held by island communities. Yet, as exploration licenses are granted and discussions progress, the stakes remain high, embodying the intricate dance between opportunity and responsibility in the realm of deep-sea mining.

Thus, the quest to extract ocean riches persists, packed with hopes and fears, shedding light on the broader implications of how developing nations choose to navigate their futures amidst the waves of change.