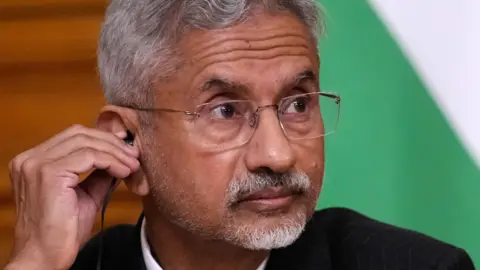

This is a time for us to engage America, manage China, cultivate Europe, reassure Russia, bring Japan into play, draw neighbours in, extend the neighbourhood and expand traditional constituencies of support, Indian Foreign Minister S Jaishankar wrote in his 2020 book The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World.

For over a decade, India has styled itself as a key node in a new multipolar order: one foot in Washington, another in Moscow, and a wary eye on Beijing.

But the scaffolding is buckling. Donald Trump's America has turned from cheerleader to critic, accusing India of bankrolling Moscow's war chest with discounted oil purchases. Delhi now faces the sting of Trump's public rebuke and higher tariffs.

With multipolarity fraying, many say Prime Minister Narendra Modi's planned meeting with Xi Jinping in Beijing on Sunday looks less like triumphal diplomacy and more like pragmatic rapprochement.

Yet, Delhi's foreign policy is at an uneasy crossroads.

India sits in two camps at once: a pillar of Washington's Indo-Pacific Quad with Japan, the US and Australia, and a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the China and Russia-led bloc that often runs counter to US interests. Delhi buys discounted Russian oil even as it courts American investment and technology and prepares to sit at the SCO table in Tianjin next week.

There's also the I2U2 - a grouping of India, Israel, the UAE and the US that focuses on technology, food security and infrastructure - and a trilateral initiative with France and the UAE.

Analysts say this balancing act is no accident. India prizes strategic autonomy and argues that engaging with competing camps gives it leverage rather than exposure.

Hedging is a bad choice. But the alternative of aligning with anyone is worse. India's best choice is the bad choice, which is hedging, Jitendra Nath Misra, a former Indian ambassador and currently a professor at OP Jindal Global University, told the BBC.

When it comes to Russia, India has shown little inclination to bend to US pressure. Discounted crude from Moscow remains central to its energy security. Jaishankar's recent visit to Moscow signalled that despite Western sanctions and Russia's deepening dependence on China, Delhi still sees value in keeping the relationship warm - both as an energy lifeline and as a reminder of its foreign policy autonomy.

Yet, history suggests that even serious rifts have not derailed relations when larger interests were at stake. The deeper question, as analysts now argue, is not whether ties will recover but what shape they should take.