Earlier this month, a Palestinian diplomat called Husam Zomlot was invited to a discussion at the Chatham House think tank in London.

Belgium had just joined the UK, France and other countries in promising to recognize a Palestinian state at the United Nations in New York. And Dr Zomlot was clear that this was a significant moment.

What you will see in New York might be the actual last attempt at implementing the two-state solution, he warned.

Weeks on, that has now come to pass. The UK, Canada, and Australia, traditionally strong allies of Israel, have now taken this step.

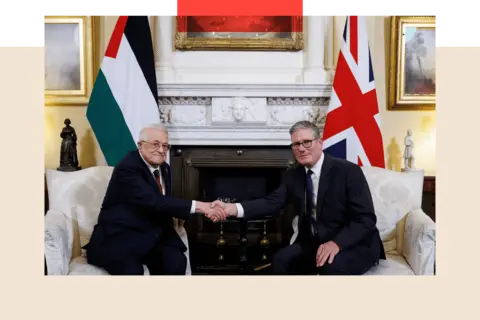

Sir Keir Starmer announced the UK's move in a video posted on social media.

In it, he said: In the face of the growing horror in the Middle East, we are acting to keep alive the possibility of peace and of a two-state solution.

That means a safe and secure Israel alongside a viable Palestinian state - at the moment we have neither.

More than 150 countries had previously recognized a Palestinian state but the addition of the UK and other countries is seen by many as a significant moment.

Palestine has never been more powerful worldwide than it is now, says Xavier Abu Eid, a former Palestinian official.

The world is mobilized for Palestine.

But there are complicated questions to answer, including what is Palestine and is there even a state to recognize?

Four criteria for statehood are listed in the 1933 Montevideo Convention. Palestine can justifiably lay claim to two: a permanent population (although the war in Gaza has put this at enormous risk) and the capacity to enter into international relations - Dr Zomlot is proof of the latter.

But it doesn't yet fit the requirement of a defined territory.

With no agreement on final borders (and no actual peace process), it's difficult to know with any certainty what is meant by Palestine. For the Palestinians themselves, their longed-for state consists of three parts: East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip. All were conquered by Israel during the 1967 Six Day War.

Even a cursory glance at a map shows where the problems begin. The West Bank and Gaza Strip have been geographically separated by Israel for three quarters of a century, since Israel's independence in 1948.

In the West Bank, the presence of the Israeli military and Jewish settlers means the Palestinian Authority, established after the Oslo Accords peace deals of the 1990s, administers only around 40% of the territory. Since 1967, the expansion of settlements has eaten away at the West Bank, breaking it up into an increasingly fragmented political and economic entity.

Meanwhile, East Jerusalem, which Palestinians regard as their capital, has been ringed with Jewish settlements, gradually cutting off the city from the West Bank.

Gaza's fate, of course, has been much worse. After almost two years of war, triggered by the Hamas attacks of October 2023, much of the territory has been obliterated. But as if all this wasn't enough to fix, there's a fourth criteria laid down in the Montevideo convention that is needed to recognize statehood: a functioning government. And this marks a great challenge for Palestinians.

Back in 1994, an agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) led to the creation of the Palestinian National Authority, which exercised partial civil control over Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank.

But since 2007, following a bloody conflict between Hamas and the main PLO faction Fatah, Palestinians have been ruled by two rival governments: Hamas in Gaza and the internationally recognized Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, whose president is Mahmoud Abbas.

That's 77 years of geographical separation and 18 years of political division: a long time for the West Bank and Gaza Strip to drift apart. Palestinian politics has ossified in the meantime, leaving most Palestinians cynical about their leadership and pessimistic about the chances of any kind of internal reconciliation, let alone progress towards statehood.

The last presidential and parliamentary elections were in 2006, which means that no Palestinian under the age of 36 has ever voted in the West Bank or Gaza.

That we haven't had elections in all of this time just boggles the mind, says Palestinian lawyer Diana Buttu.

We need a new leadership.

In the wake of the war which erupted in Gaza in October 2023, the issue has become even more acute. Faced with the deaths of tens of thousands of its citizens, Abbas's Palestinian Authority, watching from its headquarters in the West Bank, has been largely reduced to the role of helpless bystander.

Tensions within the ranks of leadership date back years. When the PLO chairman, Yasser Arafat, returned from years in exile to lead the Palestinian Authority, local Palestinian politicians found themselves mostly sidelined. Insiders came to resent the domineering style of Arafat's outsiders. Rumors of corruption in Arafat's circle did little to enhance the PA's reputation. More importantly, the newly formed Palestinian Authority seemed incapable of halting Israel's gradual colonization of the West Bank or delivering on the promise of independence and sovereignty raised tantalizingly by Arafat's historic handshake with former Israeli prime minister Yizhak Rabin.

The subsequent years were dominated by failed peace initiatives, the continued expansion of Jewish settlements, violence by extremists on both sides, Israel's political slide to the right, and that violent schism in 2007 between Hamas and Fatah.

One figure did emerge, however: Marwan Barghouti. Born and raised in the West Bank, Barghouti emerged as a popular leader during the second Palestinian uprising, before being arrested and charged with planning deadly attacks against Israelis. Despite being in an Israeli prison since 2002, recent polls show that 50% of Palestinians would choose Barghouti as their president.

While his name appears prominently on the list of political prisoners that Hamas wishes to negotiate for, Israel has shown no sign of willingness to release him.

In light of recent developments improving international recognition of Palestine, the current leadership infrastructure remains in disarray. Questions of future governance and leadership only amplify the pressing need for a coherent strategy to advance Palestinian statehood amid ongoing conflict and fragmentation.