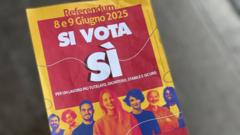

With the referendum proposing to reduce the naturalization process from ten years to five, many, including long-term residents like Sonny Olumati and Insaf Dimassi, are advocating for a "Yes" vote. However, the Italian government remains largely indifferent, as Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni boycotts the vote while framing the existing citizenship laws as sufficient.

Italy's Citizenship Referendum: A Divided Nation

Italy's Citizenship Referendum: A Divided Nation

The recent national referendum on Italian citizenship reveals deep societal divides and the ongoing struggle for recognition among longtime residents.

The Italian citizenship landscape is fraught with contention as the country approaches a national referendum aimed at reducing the citizenship application timeframe from ten years to five. Those advocating for a "Yes" vote see the proposed amendment as a lifeline for long-term, foreign-born residents who have called Italy home for years. Among them is Sonny Olumati, a 39-year-old dancer and activist who was born in Rome but has yet to be recognized as an Italian citizen.

Sonny describes his emotional plight, emphasizing that not possessing citizenship feels akin to rejection from his own country. He states, “I’ve been born here. I will live here. I will die here,” yet, without citizenship, his existence hinges on the status of his residence permit. His voice echoes the sentiments of many lobbying for changes to the citizenship law, which they argue should align with the more progressive policies of other European countries.

Despite the apparent urgency and need for a reform, the response from the current government, led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, has been dismissive. Meloni has openly declared her intention to boycott the referendum, claiming that Italy's existing citizenship laws are already sufficiently accommodating. Critics of her administration see this as part of a broader strategy to suppress awareness and turnout for the referendum.

The referendum not only seeks to accelerate citizenship for qualified applicants, but it also serves as a reflection of Italy’s evolving identity in the face of rising numbers of migrants and refugees. Even though the proposed law maintains strict criteria, such as language proficiency and a clean criminal record, it represents a shift in perspective—one that seeks to reframe long-term residents from being perceived as outsiders to recognized citizens.

Carla Taibi from the liberal party More Europe, one of the referendum's supporters, emphasizes that up to 1.4 million individuals could qualify immediately should the law pass. Their efforts focus on the idea that these individuals contribute substantially to Italian society, making the case for their naturalization all the more urgent.

Amid this backdrop, other voices, such as that of Insaf Dimassi, also resonate with relatable frustration. Born to immigrant parents in Bologna, Insaf shares her journey of navigating the complexities of citizenship, illustrating the double life of existing in limbo—part of a nation yet perpetually excluded from full societal participation.

With voters encouraged to ponder their stances, there appears to be an absence of a substantial "No" campaign against the referendum, which critics claim reflects a strategy by the hard-right government to minimize turnout and ultimately frustrate any potential progress. This calculation has been interpreted by some as a veiled dismissal of democracy, casting a shadow over the legitimacy of the referendum process.

As the referendum approaches, hopes for a transformative outcome dwindle amid government indifference and societal division. Nevertheless, advocates like Sonny maintain that this vote is just the first step toward establishing a place for their community within the broader Italian narrative, continually striving for recognition and rights in a land they have long embraced as home.